Illustrations by Mark Kowalchuk

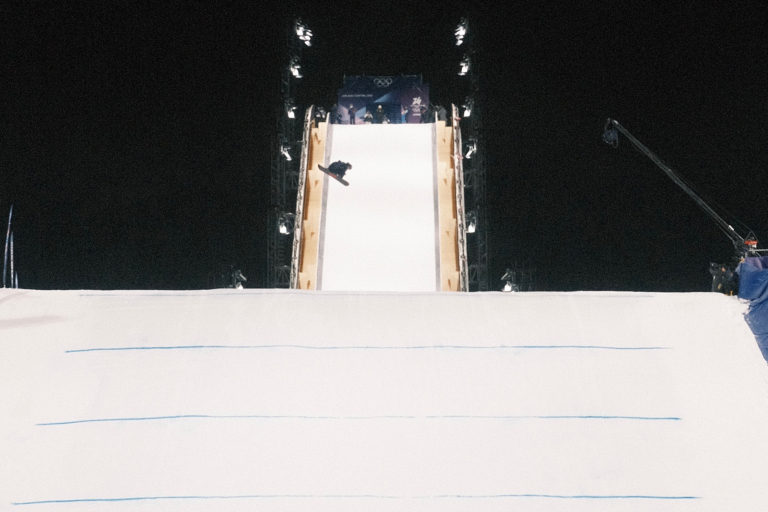

Make no mistake, snowboarding is a risky activity, especially if you thrive on the excitement of going faster, jumping further and becoming more creative than the last time you went. And at the end of the day, there is but one question. Why? Why do we willingly put ourselves in the face of serious danger time and again? What is it about snowboarding that drives this constant need to progress beyond our physical and mental boundaries?

As human beings we are ceaselessly driven to explore the limits of our potential. This is a built-in evolutionary trait and basically unarguable. Unquestionably, this progression is facilitated by the desire to overcome our fears. After all, if none of us were able to conquer that which frightened us, we would remain as children, afraid of the dark if only because the reality of our surroundings isn’t illuminated. But I think a discussion of how and why moving beyond fear is good for mind and body has been covered in detail by a good hundred years of modern psychology, if not the common sense understanding that it is the very precept behind any kind of transcendental growth.

I would rather explore a couple different areas instead. First, what happens to us when we are in that fear state? Or more specifically, is there an actual process that occurs which allows us to perform physically in ways superior to normal states of consciousness? And second, what really drives us to overcome fear? Is it a desire to put fear behind us for the sake of personal growth, or is it a desire to experience the feelings associated with overcoming fear? That is to say, are we simply chasing pleasure at a high cost?

In biological terms, there are a few interesting things to note when understanding fear — good things — stuff that accounts for the sometimes unexplainable, otherworldly experience that pervades a fearful physical experience. We’ve all had those moments on a snowboard where we are at a loss to explain what just happened after either summoning the courage to try something previously thought impossible or having been caught by surprise and narrowly escaping certain annihilation.

First, our response time quickens. Inside the do-or-die experience we harness an almost automatic resolve, a force so compelling and alien to our normal waking state it’s as if another being altogether is steering the ship. This is the ancient survival mechanism at work, a master key to our untapped potential and superhuman abilities; it’s our hidden stash of mongoose power that speeds our reaction time tenfold. Actually, it’s far more than that. Studies have shown that while in normal circumstances it takes about half a second for awareness of an outside event to enter consciousness, the fear system can begin responding in much less time — just twelve-thousandths of a second. So when we say we had a lighting quick response, it’s no joke.

Next comes strength. The fact is, fine motor skills like threading a needle or finding a key to unlock your car door as you are approached by a convent of young Mormon boys actually decline under pressure. This is otherwise known as being paralyzed by fear. Gross motor skills however, those used to run or jump, light up with berserker strength. One explanation for this may lie in the fact that the brain releases powerful analgesics during acute stress. The resulting painkilling effects combine to delete any pain associated with going that extra yard. In turn, the bar of what we can physically endure is raised.

The next thing to consider is focus. When we willingly, or unwillingly, are in a position of impending necrosis, the subconscious mind instantly gets to work behind the scenes by narrowing attention only to things that are extremely important. In other words, we eliminate our tendency to over-think the situation. For example: If an exposed rock suddenly appears during the course of your descent, your brain isn’t going to try and discern whether it’s granite or limestone, it’s going to act in a singular way to ensure you don’t hit it. It releases a potent neurotransmitter and hormone called norepinephrine — the brain’s version of adrenaline. Norepinephrine causes the mind to be more alert and active when attention is essential. The Adderall I just took to ensure this article makes sense is manipulating my cellular uptake of this neurotransmitter to that same effect.

Another phenomena associated with fear-based response is the experience of time dilation, or the idea that time somehow slows down during moments of extreme stress. However intriguing the idea of slowing down time for the benefit of our survival seems, what studies show is something unexpected. While many people report a vivid, extraordinarily detailed account of what happened during a terrifying event, the truth is that we simply remember more than in normal states of consciousness. With the release of norepinephrine a part of our brain called the hippocampus is stimulated — a region associated with memory formation. So essentially, time isn’t slowing down, we’re just remembering more — a handy tool when up against a similar circumstance and we need to draw upon past experiences for reference.

Read also: Power of fear: A Bode Merrill interview

Finally, the most astonishing, if not ironic thing that happens when we are pitted in a survival situation is an all-pervading calm that sometimes takes over. Essentially, when the piper is expecting payment all emotion appears to vanish. You are acutely aware the situation is critical and it’s inherently known that cross examination is pointless. In turn, the brain cuts all links to unnecessary avenues of thought and allows for a state of mind that can take care of business. Only in this relaxed state of mind are we able to make the unimpaired decision that could amount to us living to ride another day. How cool is it that when up against fear we can instinctively become fearless?

What these phenomena amount to is a singularly unique experience, which from an evolutionary standpoint is here to ensure our survival in the case we find ourselves pitted against the sketchiest of scenes. It just so happens that it is also a place where we find what we are really made of, something often more gratifying than everyday life.

The question then becomes as snowboarders — or in psychological terms, pathological risk takers — how do we make everyday life more gratifying as not to look for pleasure in the most consequential places?

Understanding the effects of the fear dynamic, why it gives us the power it does and consequently the emotions to which it gives rise is simply the superficial layer of a much deeper idea. The important thing to understand is why we consciously choose this. Why do we risk so much for that feeling?

Is it to experience life at its most intense? Is trying to reconcile the equation of skill and experience against physical danger the measure of a life fully lived?

Buddhist, yogic and most Eastern philosophy tell us explicitly that chasing pleasure all of the time will only bring you suffering. The reason is simple: If we come to rely on pleasurable activities as our means of happiness, what happens then when we are unable to fulfill these happy-making activities? Naturally, we yearn for them, base our existence on reaching for them and in the case of snowboarding, put our well-being at risk in the pursuit of an experience that tops the last. It’s an addiction to pleasure at the highest level — there’s no getting around that one.

Whether or not attaining a Buddha nature is appealing to you, it’s a valid lesson to understand. The other side of the coin is that by facing our fears we undoubtedly become stronger people. Nowhere is this more certain than overcoming emotional barriers. We all know that problems do not just disappear; we have to deal with them. And dealing with them inevitably involves facing a certain level of fear. When talking about the material world however, as in the physical progression of learning a trick or riding bigger lines, the victories are hard fought by overcoming fearful obstacles one step at a time. After all, if we were too scared to try anything new we would not graduate beyond the bunny slopes. At the same time, there is no arguing the fact that pushing your limits offers valuable insights. The concerning part here is that at a certain point the expedition becomes deranged. Whether you believe you are conquering fear for the sake of raw experience or are unconsciously chasing a cyclical pattern of emotional exaltation, there is a physical limit to what we can do. Yes, those seas can be charted, but it’s old news that the further you explore that dangerous territory so rises the probability of the ship sinking.

In the end, eliminating emotional fear is paramount to a life well lived. Deliberately putting yourself in harm’s way for the attainment of an emotional hit on the other hand, that sounds like straight up addiction.

There is no denying that in the face of danger we have a built-in program that aids in our survival, albeit one with some seriously trippy side effects, least of which may be a dependence on the very mechanism that is intended to save us from death. Is there something in human nature that has always directed a select few towards this deadly game? Has it propelled a certain part of our evolution? Did some of our more radical ancestors willingly taunt Saber-toothed Tigers for the resulting thrill of being chased? If so, they must have reveled in the onset of intense emotions that followed and stroked the egos of their fellow proto-man; “Did you see Güngo poke tiger today… so sick!”

Or have we sadistically learned to harness the power of fear’s biological and psychological secrets to fill the voids of an existence that we find unsatisfying? Does establishing a need for an experience that provides elation require then that the need must be met? If so, what’s your price?

Originally featured in Snowboard Magazine: The Detour Issue